Perfect Competition Is Nonsense

I’m going to start by parroting a point made many times by many people. Perfect competition as described by economists doesn’t exist, and it likely cannot exist. But in understanding the flaws of that model, we can better understand the range of competition that does and, more importantly, can exist.

The Assumptions of Perfect Competition

The standard economics model of perfect competition concludes that enterprises make no profit. But, enterprises make profits all the time. Therefore, at least some of the assumptions of the perfect competition model have to be wrong. But what are those assumptions? They are often described as follows:

Many Buyers

Many Sellers

No Barriers to Entry or Exit

Everyone Sells Identical Products

Everyone Has Perfect Information

The Path Dependency of Assumptions

Those five assumptions are often listed as though they were independent of each other. But they’re obviously interrelated.

In order for there to be many buyers and sellers, there must be few barriers. In order for there to be few barriers to entry, people must have access to similar information.

Indeed, the central thesis of this post is that Perfect Information does a lot of the heavy lifting in the perfect competition model.

For Example: if the process to make a new material is a secret. Others can’t copy the manufacturing process. Therefore, there is a barrier to entry. Therefore, many sellers are impossible. Therefore, identical products are impossible.

What can we conclude from this? If many enterprises are profitable, and many of the assumptions of unprofitable conditions are path dependent on perfect information, then the KEY to profit must include imperfect information.

Another way to say this: secrets can be very profitable.

That statement is something that is uncontroversial. Everyone has heard the cliche about how information is power. But what may be less well understood is why that cliche is so true.

Why Are Secrets Profitable?

One model for all economic activity is to interpret every action as a trade.

In building a company, one often trades capital (money) for other forms of capital and also for labor. The goal is to eventually re-trade distilled products derived from those forms of capital and labor for money (capital) again.

In trading in financial markets (investing), one trades capital for other types of capital, in markets of differing liquidity.

But the only reason to do a trade is because you think you know more than your counter-party. You feel you have access to some secret (some hidden way to generate synergy, some market information, some fundamental insight, some scientific breakthrough).

If both parties were equally informed, there would be no reason to buy an asset. After all, in a world with perfect information, all assets would be perfectly priced and no trade would ever be profitable. Indeed, no trades would ever happen. The BASIC logic of almost every transaction is that BOTH sides think they know more than the other. They both have access to some secrets (almost like a hand of poker where both parties have private information). The question of every transaction is whose secret is MORE valuable.

That types of secrets underlying every trade on each side can vary. Maybe its about the market opportunity or about the asset itself. Maybe its about what other people think. Maybe its about what other people will soon think. Maybe its a combination of a lot of little secrets. Maybe its all of the above.

Secrets + ?

But information on its own is obviously not sufficient. If that were the case, the world’s wealthiest people would be reporters, scientists, and academics. Clearly, they are not. As important as secrets are, there is some friction in the translation of secrets to profit.

The Profit Path: The Execution Vector

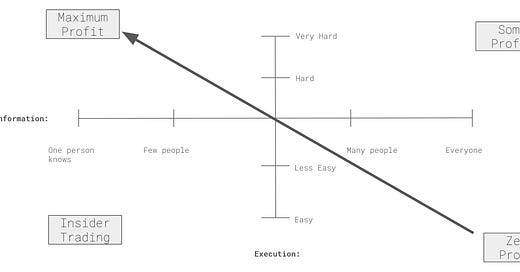

This is a two-axis model that I hammered out recently that I find simple and helpful.

Ultimately if we think about every economic activity as a trade or a series of trades, then the ease in executing those trades (think transaction costs, coordination costs, management difficulties, etc) is another relevant vector determining profitability. You might frame execution difficulties as barriers to entry.

Another way to frame the execution axis is as LIQUIDITY. In liquid markets (think the public stock market) finding counter-parties is easy. In illiquid markets this is not so. Think of labor markets, hiring quality people that fit with your culture is very difficult.

Combining these two ideas in tandem: secrets + the ease of executing on those secrets is powerful.

If you’re trading on secrets in public markets, you might be put in jail under insider trading laws.

If you’re in a market space where everyone is doing the same thing and the execution is easy, you will find yourself ruined.

If you’re able to execute on a high level (maybe because of some psychological quirk like those exhibited by Tiger Woods, Cristiano Ronaldo, or Michael Jordon), then you might not need too many big secrets to be successful.

BUT the obvious quadrant you want to be in for the most profitable enterprises is the top-left. If you have the capability to execute trades in illiquid markets AND have some fundamental secrets of deep value, you will make a lot of profit.

Like every simplification, this two axis model has its own problems. It assumes that execution has nothing to do with information. But good operators often have their own set of tricks that help them execute. Sales tricks, management experience, sources of arbitrage, etc. On some level, execution is its own bundle of secrets.

If we were to embrace complexity, the graph would have a lot more information axes instead of any execution axis. But, let’s not do that. Simplification can sometimes be conceptually helpful.

Pixar as Top-Left

One example I like on the top-left quadrant is the story of Pixar. When Steve Jobs bought the company from George Lucas, few people knew the quasi-secret that computer graphics could result in incredible feature length movies. Steve Jobs then poured massive amounts of his own capital for years to permit a very arduous execution path to that first release of Toy Story. That combination, the secrets of the value of computing in producing films + the ability to execute in a series of trades in deeply illiquid markets (labor markets for programmers, creatives, voice actors, distributors, etc) is what made Pixar so successful. It’s ultimately what made Steve Jobs the biggest shareholder in Disney.

The Secret is Finding Secrets

A lot of people peddle courses on how to get rich. There’s an entire ecosystem of grift lords like the Rich Dad Poor Dad guy who sell content trying to teach people how to get rich. But if the hidden secret to wealth was something you could obviously learn and easily execute on, you would find yourself in the bottom right quadrant. The secret would no longer be a secret. You would find yourself in a world resembling perfect and ruinous competition. Trying to get rich of off obvious sources of information is really dumb.

One shouldn’t listen to these people. The only insight that can be publicly available is the meta-secret that there are secrets. Finding them and executing on them is your job.