The Healthy Cigarette

“What cigarette do you smoke, Doctor?” — R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company Advertisement (1950)

There have always been incentives for institutions to lie. Take for example, Big Tobacco. Already in the 1940s, some physicians were raising links between cigarette consumption and cancer. In response, Big Tobacco companies rallied with an advertising campaign determined to further the perception that cigarettes were actually healthy.

Confronted with the fact that cigarettes killed their consumers. Big Tobacco went on offense on the same issue.

Of course, the attempt by Big Tobacco to create the public perception of a health benefit from cigarettes wasn’t new. Indeed, going back to the 1920s Lucky Strike routinely advertised based around the idea that cigarettes made you skinnier or somehow fought cough and irritation.

This Big Tobacco strategy somehow persists. Today, Altria’s website opens with a strong mission statement suggesting that the company is: “Moving Beyond Smoking”. Vaping companies like Juul have touted the effectiveness of e-cigarettes in helping people quit cigarettes, thus proclaiming e-cigarettes to be a healthier alternative.

Strategically, if you sell a product that is fundamentally inefficient, your incentive is always to lie about that fact. Cigarettes are inefficient. For the nicotine buzz, people trade away years in life expectancy. But it behooves Big Tobacco to obscure that.

Nevertheless, Cigarettes have been openly exposed as an anti-technological product. Still, Big Tobacco companies are far from the only anti-technological institution in our society. Instead, they are just the most obvious one. An easy target for political attack. What about all the others?

The truth is that vast swaths of American society are organized in ever less efficient ways. But this often isn’t recognized. After all, the inefficient institutions that surround us have every reason to distort our perception of how inefficient they really are.

The only way out is a critical reexamination of our most powerful institutions. This is a reexamination that our co-opted media, political, and nonprofit institutions are far too unwilling to undertake. We, as a country, suffer deeply from it.

The Definition of Technology

The classical definition of technology is doing more with less.

Take the classical example of the lever. The lever allows its user to expend less force to lift objects. As Archimedes famously quipped, “Give me a lever long enough and a fulcrum on which to place it, and I shall move the world.” Archimedes wasn’t boasting about his own strength. Instead, he was highlighting the power of technology to let him do more work with less effort.

Technology is definitionally about input versus output. Anything that increases output for a set amount of input is technology. Anything that decreases input for a set amount of output is technology.

A toaster is technology because it allows humans beings to quickly heat bread. On the other hand, building a fire from scratch to heat your bread is anti-technological compared to a toaster. It just takes way more human effort.

Defined in this way, technology doesn’t just have to be a machine. Social systems can be a form of technology. A system of property rights that increases economic output for the same amount of human effort is a form of technology. A system of government that reduces corruption is technology. Technology is all around us.

To drive this home, take a look at the following diagram:

In this grid, the baseline is taken as given. For that baseline, putting in more inputs, while achieving less output is anti-technology.

The bottom left quadrant, anti-technology, is like building a fire to toast your bread. More-Less is always anti-technology.

The top right quadrant, the traditional definition of technology, is like using an even more efficient toaster than the ones that exist today. Imagine some sort of futuristic laser toaster that uses almost no energy. Less-More is always technology.

So then what are the other two quadrants? Well, sometimes you can decrease the amount of input and get less output. But that might still be considered technological. Let me give you an example.

Let’s say you decrease the amount you study by A LOT. But your grades only decrease from an A average to an A- average. That might be a worthwhile tradeoff. Maybe even a technological tradeoff, because your efficiency has gone up. Less-Less can sometimes be technological.

Similarly, sometimes you can put a little more input in, to get way more output. For example, if you change the hours you work by 5 percent but you increase earnings by 500 percent. That can still be technological. More-More can sometimes be technological too.

Quantifying Technology

Economists use a term called Total Factor Productivity, or TFP, as an analog for technology. As the Bureau of Labor Statistics explains: “Total factor productivity is calculated by dividing an index of real output by an index of combined units of labor input and capital input.”

TFP is economic jargon for the same concept highlighted above. What are we putting in? What are we getting out? TFP is that ratio.

Importantly, TFP embodies the point addressed earlier, namely that social organization can be technology too. As one IMF working paper from 2015 corroborates: “In general, TFP captures the efficiency with which labor and capital are combined to generate output. This depends not only on businesses’ ability to innovate, but also on the extent to which they operate in an institutional, regulatory, and legal environment that fosters competition, removes unnecessary administrative burden, provides modern and efficient infrastructure, and allows easy access to finance.”

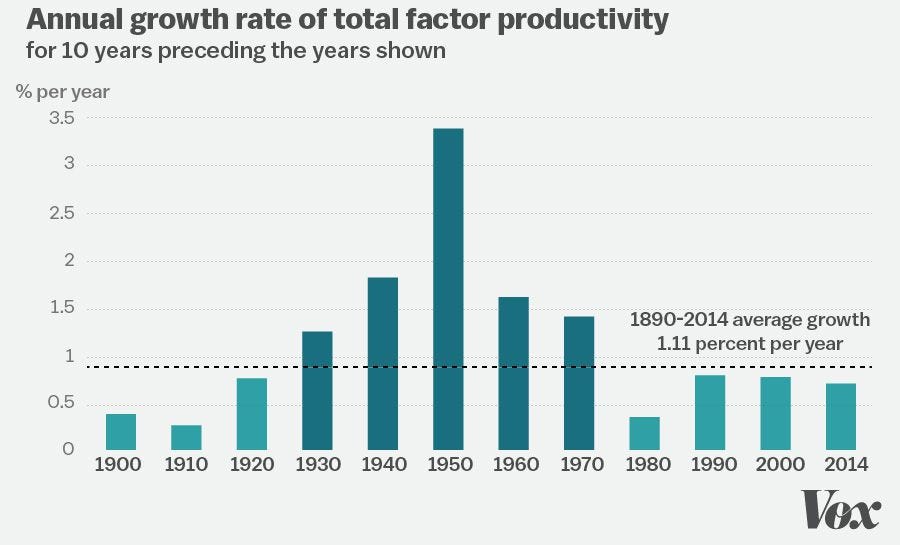

Slowdown in TFP

Of course, the staggering truth, one that is too little discussed, is that growth in TFP has been slow for decades (going back to at least the 1980s).

Why Are We Stuck?

There are all sorts of theories for why TFP growth is stalled. The Silicon Valley types seem to believe that TFP doesn’t measure productivity growth correctly. People like Robert Gordon suggest that TFP growth in the 1950s was just an abnormality, and that we shouldn’t expect technological progress in our institutions and products as we once did.

I have a fundamentally different view. Namely, that there is a ton of low hanging fruit to reorient our society in a more technological direction. But, getting political consensus to make that happen is often difficult. All the low hanging fruit is in areas where monopoly concentration and regulatory capture has made innovative challengers extinct. To break the regulatory vice-grip, a political mandate needs to be created to unlock these sectors again.

But the problem is that a political mandate is difficult to rally in a world where people are so often and dramatically misled by the prevailing institutions. Remember Big Tobacco lying about the health benefits of cigarettes? Well they were just following the same strategy that The College Cartel, Big Oil, and many other cartels and monopolies use: obfuscation.

Any product or institution that is anti-technology has a reason to lie about that. These institutions instead pretend to be technological in one of the three forms highlighted above.

The College Cartel Example

As I’ve written about in my book, The College Cartel, higher education in the United States is fundamentally anti-technological. Tuition costs rise faster than the rate of inflation with absolutely no evidence that the education is getting any better. Indeed, many claim that the quality of education is actually getting worse.

So how do colleges, elite and non-elite, obscure that fact? They continue to claim that while education costs are rising, the earnings premium of a college degree is too. They try to shift the public perception of their product from MORE-LESS, to a technological form of MORE-MORE.

Of course, the earnings premium narrative is deeply deceptive. There is plenty of evidence that the growth in the earnings premium doesn’t come from an increase in the value of a college education but rather the brutal collapse of jobs in America for those without a college degree.

Of course, by focusing attention on the output side of the college equation, schools can ignore their own fundamental inefficiency with the inputs they select. They don’t have to address bloated administrations. They don’t have to address the building of lazy pools and worthless facilities completely unrelated to education. They don’t have to address the inherently slow pace with which information technology is being integrated into campus life.

As long as they can obfuscate and use the US Government to raise entry barriers to credentialism, they will.

The Big Oil Example

The Big Oil example is also interesting. Today, there is a steady political consensus that climate change is real and man-made. Nevertheless, there is also an increasingly pervasive narrative that Americans ought to support the ESG movement whereby Big Oil companies take some of their profits and invest them in R&D around Geothermal, Solar, or Wind energy.

This ESG frame turns the anti-technological oil sector into the vehicle for a green technological transformation. It shifts a MORE-LESS sector into a LESS-MORE sector in the public mind.

Look for example at this headline in Forbes from 2022: ESG Investors Should Support Big Oil. By pretending that Big Oil is a means to a more technological end, the sector obscures its fundamentally anti-technological bent. Yet, increasingly, Americans are being taken along for the ride.

Of course thats not all Big Oil does. They also move to classify fossil fuels as technological. Frames like clean coal, green natural gas, and others help obfuscate what is really happening. Take, for example, this story from Ohio.

Lastly, there’s some evidence that Big Oil allies have subsidized so-called green groups in their war on nuclear energy. This type of dark move prevents nuclear energy from ever being deployed at scale, by increasing the regulatory burden to the point where nuclear can never achieve liftoff. By framing nuclear energy as anti-technological, despite the theoretical truth that nuclear offers the best energy-density of any commercial technology, Big Oil has been able to keep a powerful potential entrant out. Again, the strategy is one of lying.

Where We Go From Here

We’re in desperate need of a new political movement oriented around dismantling the state protections granted to anti-technological institutions like the Ivy League or Big Oil. Nor are those the only sectors with an anti-technology bent. Another obvious problem is Big Pharma with its patent protections and regulatory capture of the FDA to raise the cost of entry. Healthcare, housing, education, energy, many massive swaths of America are fundamentally anti-technology.

We can no longer wage a case by case battle for public support. We need a broader political narrative around the fundamental issue of American stagnation and the role that lying from big incumbents plays in securing that stagnation. We also need it soon.